A Pandemic Birthday

In celebration of the Department of Journalism’s 50th year, five alumni talk about their careers and how COVID-19 affected them.

Story by Jaya Flanary

I wake up at 6 a.m. on the flattest mattress I’ve ever slept on. The room smells like exactly what it is: a musty, college dorm. But, I was only 16, so I thought it was cool to sleep poorly and shower communally.

The first time I walked Western Washington University’s campus I was attending the Washington Journalism Education Association’s Summer Camp, better known as J-camp. It’s a four-day intensive that teaches high school students the ins and outs of journalism.

It was mid-August, when the air is warm and the days are long, and I spent it in my element: learning feature writing and InDesign. When I walked between classes, I thought about how I could end up at Western. I could get my degree in journalism.

In 1970, the journalism major was established, and was taught as a program within the English Department. In 1976, the program expanded, becoming the Department of Journalism, as the college grew.

As the program expanded, journalism professors such as Gerson Miller, Ted Stannard, Pete Steffens, Lyle Harris, Carloyn Dale, Floyd McKay and Tim Pilgrim made lasting impacts on their students. Three tracks were created within the major: News Editorial, Public Relations and Visual Journalism. The Communications Facility Building was built, faculty changed, students came and went.

In 2020, seven years after I left J-camp, I took my journalism capstone classes entirely online. I met with my professors on Zoom and did my homework from my bedroom. And as I wrapped up my academic career, WWU’s journalism major celebrated its 50th birthday.

As we all know, a birthday pandemic is not too fun. So, to celebrate this milestone, I interviewed five journalism alumni — one from each decade — to talk about how they got from where I am now to where they are now. And, of course, how where they are has changed since COVID-19.

Carolyn Price (1977)

A WWU volleyball player returns from a weekend tournament and rushes home to Ridgeway Commons. Hunched over her high school graduation present, a Smith Corona typewriter, she writes up an article about the games. Next, she hitches a ride to Birnam Wood to interview the field hockey coach for her other Western Front beat. Back at her dorm, she writes up a second sports story late on a Sunday night.

It is 1973, and her name is Carolyn Price.

Price sprints down High Street, both stories in her hands. Ignoring the Viking Union’s main entrance, she heads straight toward the bottom floor windows and knocks. Her editors open the window and Price climbs in. Two days later, her stories will be published.

“It was like a college newspaper office in the 70s,” Price said. “I didn’t really know how cool that was, but I knew I had a lot of fun.”

Price graduated in 1977, the same year Western Washington State College became Western Washington University. “The thing I remember most is that our quarterly tuition went up from $169 a quarter to $225 or something,” Price said.

During her academic career, she worked on both The Western Front and Klipsun Magazine. Her professors included Pete Steffens, Gerson Miller and Ted Stannard — who she remembers always wore a safari vest with “21 pockets in it” to hold film canisters.

Stannard taught students to keep two frames at the end of their rolls of film, because as a journalist, you never know what you’ll come across. This trick helped Price during her first job out of college at the Lynden Tribune, when there was an airplane collision she heard on the police scanner. Price, then 22, brought her camera to the scene where three people had died. The coroner asked her to photograph the bodies.

“I got some pretty nasty pictures, and pretty soon, I just couldn’t stomach it anymore. I gave [the coroner] my camera and I went and sat in my car,” Price said.

She returned to the Lynden Tribune that night to process the film in the dark room, then called The Seattle Times to inform them of the accident. They asked her to print copies, drive to Bellingham, Washington, put the prints on a Greyhound Bus and send them down to their office for publication.

Price remembers getting a check for “50 bucks or something.”

Price was the first woman in Washington to be a newspaper sports editor. Originally, she did not get the position, because it was given to her male counterpart. However, he quit two months later — with a farewell column that stated he hated following tractors going slowly up the Guide Meridian — which opened up the position again. Price was hired, at $75 less a month than her predecessor.

Over a year later, she got herself a well-deserved raise after she was offered a job at the Anacortes American Weekly. She told her editor at the Tribune that the Weekly offered her more money (they didn’t), and the Tribune matched it.

Eventually, the Lewis family, who has owned the Lynden Tribune since the 1800s, bought a monthly newspaper in Point Roberts, Washington, a pene-exclave of the U.S.

Next thing she knew, Price was selling ads, writing stories and designing pages, as well as picking the paper up at the printers and delivering it to homes and businesses. At first, she commuted between Lynden, Washington and Point Roberts (four border crossings a day), but she eventually moved to the small beach-front town to manage the monthly paper.

“That is where I really learned the skills to start my own magazine,” Price said. “If I hadn’t had that job, I don’t think I would have had the skills.”

In the mid-80s, Price was freelancing until she saw an ad in the Seattle Weekly about a bicycle tabloid based out of Redmond, Washington. She worked for the tabloid for six months and learned a lot about bicycle racing.

Once, Price was assigned to drive Olympians Mark Gorski and Nelson Vails to a track racing event. “They were staying at a local motel and it was my job to pick them up in my little 1980 Datsun pickup,” Price said.

She remembers how big the athletes’ thighs were — Gorski hanging out the passenger window and Vails straddling the gear stick.

Eventually, after talking to advertisers and readers, Price realized people were in the market for a newspaper that wasn’t just about bicycle racing. Naturally, she decided to start her own publication in competition with her former boss.

Her first issue was eight pages, published in February of 1988. Her second issue was 16 pages. Her third was 24.

“I started a neighborhood newspaper when I was 10,” Price said. “So, I’ve always wanted to do this.”

Over three decades and many iterations later, OutdoorsNW Magazine, which covers all outdoor recreation in the Northwest, is distributed throughout Washington and Oregon. In 2019, they switched from printing eight times a year to four times a year, focusing more on their digital presence, which Price said was very profitable.

In 2020, the pandemic affected the magazine because tourism, events and advertising — all things that decreased — are crucial to the publication. Price tries to stay digitally relevant by managing social media, updating the website and writing stories. “I’m just kind of taking it slow and easy right now,” Price said.

After a long and successful journalism career, Price is looking to pass the torch. The magazine is for sale, and she is seeking out potential buyers.

“I think part of my passion and my energy for what I’ve done for three decades is waning. I’m kind of tired,” Price said. “I’d like to pass along the magazine to new blood.”

- A 1975 edition of The Western Front included Carolyn Price on the writing staff.

- Carolyn Price's article on her trip to Mexico published in a 1975 edition of Klipsun Magazine.

Sarah Logan Gregory (1981)

Well before COVID-19, Sarah Logan Gregory was a self-proclaimed “pandemic interest freak.” Her bookcase is full of books about pandemics, plagues and viruses. Through her 25 years with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, her job focused on a range of infectious diseases: West Nile virus, E. coli, bird flu, swine flu, H1N1 virus and everything in between.

Almost four decades before the coronavirus, Gregory graduated from WWU with a journalism degree and a minor in psychology. She remembers the Department of Journalism providing a personal education, and that the faculty and students were “like a family.”

“I do remember Lyle [Harris] saying many times that if you’d written something that was stupid, ‘You should be picking carrots instead of being a journalism major,’” Gregory said.

After graduation, Gregory worked for a couple of newspapers, did some freelancing and got into book publishing. Eventually, she wound up working at the CDC, in the Office on Smoking and Health for 10 years. She became the CDC plain language expert, which she attributes to her journalism background.

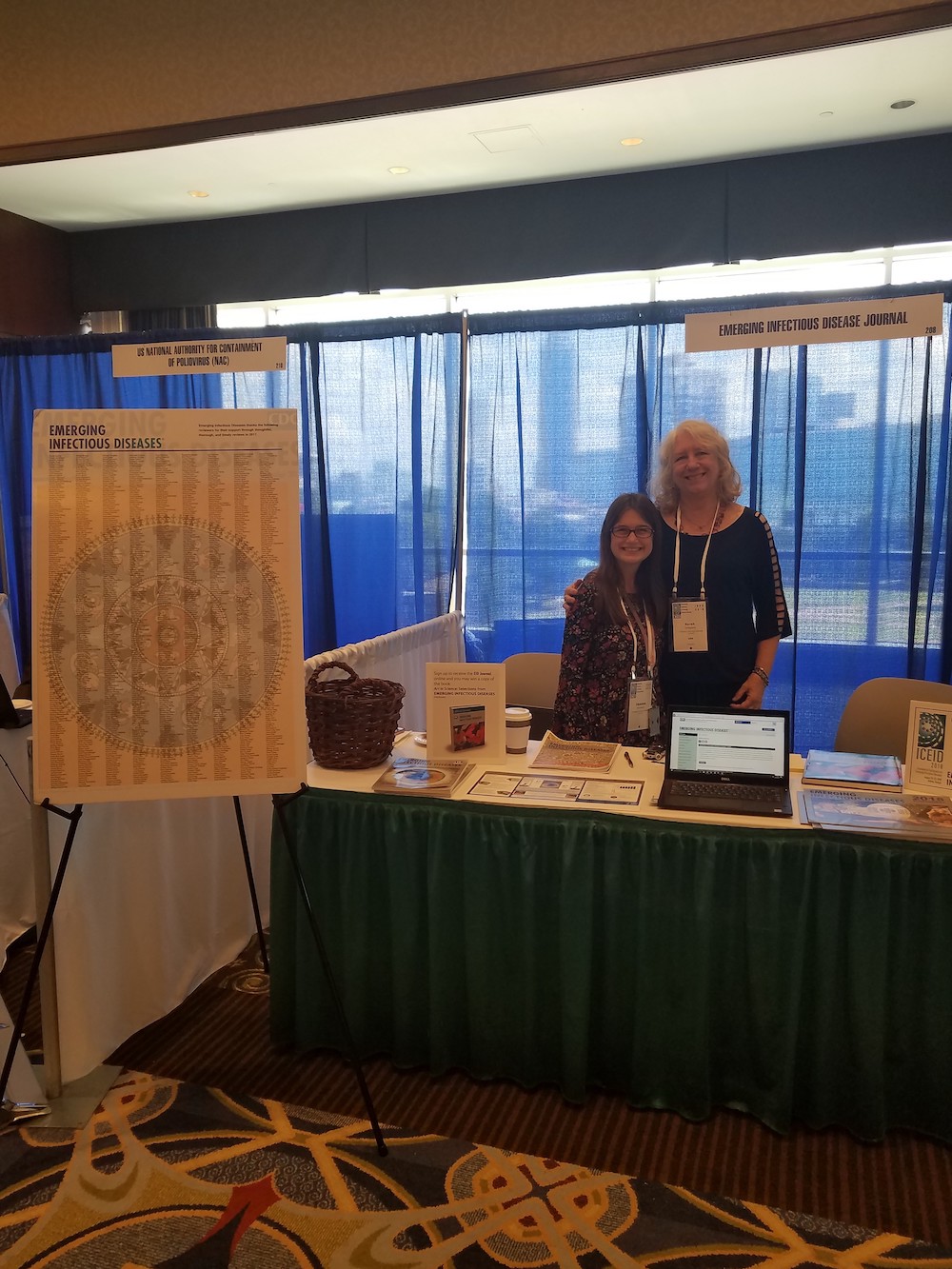

Now, she is the Lead Communication Specialist for the Emerging Infectious Diseases journal, an open-access, peer-reviewed journal published monthly by the CDC (though not a voice of the CDC). In addition to running the EID Twitter and Instagram, Gregory hosts a weekly podcast where she interviews EID contributors about their articles.

“People forget that this isn’t the only possible pandemic. There are so many things occurring in the world that are deadly and dangerous and scary,” Gregory said. “I hope I’m doing a greater service by talking in my podcasts about these other things, reminding people about diseases they need to be aware of, even things in this country.”

While the journal is scholarly and scientific, Gregory’s podcast is made for the general public, so it uses plain language and is more accessible for a wider audience. After hosting it for 10 years, Gregory feels like she has improved tremendously.

Before the pandemic, she was asked a couple of times to speak in a podcasting class at Emory University, which is near the CDC main campus. Once, Gregory noticed one student smiling during her entire presentation. The student, Deanna Altomara, ran up to Gregory after and said she wanted to be her intern.

“She is the most amazing person,” Gregory said. “So, she did a six months free internship for me, and then did an additional six months free internship. I just loved her to death, and she’s now a contract staff member on the journal.”

The journal, which has a small full-time staff, also has peer reviewers who volunteer their time. Last year, because of the abundance of COVID-19 articles, the journal had over 1,700 peer reviewers working on it. They went from publishing 40 articles a month to upwards of 70 articles a month.

2020 marked the journal’s 25th anniversary, but it was the first year it became an online-only publication — not because of the coronavirus, but because it was time to lessen the carbon footprint.

“We finally, painfully, made the decision not to print anymore, which is really sad because it was actually a beautiful journal,” Gregory said. “But we still do the cover and the Managing Editor writes a cover story about the artwork and where art and science intertwine.”

Gregory, who regularly works from home a few days a week, has been teleworking completely since March 13, 2020. She loves working from home and not having to commute. “This works great, especially for a journal. We’re all really connected. We’ve got deliverables. We’ve got deadlines. There’s no problem,” Gregory said.

Though Gregory enjoys teleworking, she misses her staff’s monthly potluck, which always had a theme. She also misses the high-end CDC audio studio, which is where she used to record the podcast. Now, she’s podcasting out of her daughter’s old bedroom.

“I’ve got to say that what I do is really, super cool. I mean, it really is. It’s a very unique job,” Gregory said. “In fact, every once in a while I’m like, ‘Oh, I just want to travel and I want to retire.’ And my daughter says, ‘Are you crazy? You have got the most unique, cool job ever.’ And I’m like, ‘Oh yeah, you’re right.’”

- Sarah Logan Gregory's article on Bellingham businesses published in a 1980 edition of The Western Front.

- Sarah Logan Gregory shown as the Editor of The Western Front in 1980.

- Klipsun Magazine's 1980 edition included Sarah Logan Gregory on the writing staff.

Erin Middlewood (1994)

One journalism professor, Lyle Harris, took his students to Bellingham City Council meetings and had them write up articles the same night. His student, Erin Middlewood, remembers that Harris would mark up the stories the next day on the overhead projector in front of the whole class.

“I wouldn’t say it was a good experience but it definitely taught and prepared us for working on a newspaper,” Middlewood said, laughing.

Middlewood’s first time working for a newspaper was when she was a child, delivering The Columbian in her hometown of Vancouver, Washington. Little did she know, she’d be the Features Editor for that same newspaper decades later.

In between, she worked on The Western Front as an editor and Klipsun Magazine as a writer. She was also featured in The Western Front in 1992 for being the Associated Students president. With a double major in journalism and political science, she was heavily involved in WWU’s debate team.

“I learned to research and synthesize information on deadline because of the [debate] competitions,” Middlewood said. “It actually really helped me learn to build stories in a logical way.”

After graduating in 1994, she put together programs for lecture series before landing a job at The Columbian. At that time, letters to the editor came in the mail, and Middlewood’s job was to type them up on a computer.

“There was talk that this thing called the internet might pose a problem for newspapers in the future,” Middlewood said. “I think the core of [journalism] is the same: finding stuff out and writing it up and making it clear and concise.”

When Middlewood took journalism classes, she had to go to the Whatcom County Assessor to look up property records — something that journalists nowadays can easily look up online. Through her career, Middlewood has seen the impact technology has made on the industry. She believes a journalist is better off as a “jack of all trades” in the field.

Eventually, she left The Columbian, but later returned as a reporter, and then began writing feature stories. Middlewood said she has always focused on the words, but has to “be ready to do anything.” The Columbian’s editors rotate weekend on-call shifts, so even if you’re primarily a writer, you must be prepared to go out and take photos for a breaking news event.

“I really enjoy features because it’s an opportunity to go in more depth,” Middlewood said.

In 2019, she became the Features Editor. Less than a year later, the pandemic hit — changing the way newspaper feature stories were written. Because large gatherings were banned, The Columbian’s Weekend section, which focused on events, was suspended. The Life section started to focus on how the pandemic changed people’s daily lives.

To brainstorm story ideas, Middlewood reads national media like The New York Times and The Washington Post, and observes how things have changed around her. In the last year, she wrote about how families are coping with children learning remotely. One of her colleagues, Scott Hewitt, wrote about Zoom fatigue; and another, Monika Spykerman, wrote about comfortably socializing during the pandemic.

“I think everyone’s tired of COVID whether you’re writing about it for the newspaper or not,” Middlewood said. “Everybody wants to move on.”

Instead of solely focusing on COVID-19 stories, Middlewood and others at The Columbian try to write every “walk of life story,” including what people are doing now instead of what they’d be doing normally, which results in a lot of outdoor stories.

“For our team, we’ve really focused on how to help people cope, how to reflect this in a sort of documentary way, but also just how to have fun,” Middlewood said.

Middlewood said in-person interviews still occur if the subject is comfortable — socially distanced, wearing masks — but most interviews happen over the phone. Working from home, Middlewood prefers phone interviews over Zoom interviews, so she can take notes. Along with herself, her husband is working from home and their kids are in school remotely.

“I’m one who actually likes to go to the office. So, I’m looking forward to being in the office with coworkers again,” Middlewood said. “In terms of my career, I’m very happy at The Columbian. It’s my hometown paper; it’s one of the few family-owned newspapers. I’m very happy.”

- Two of Erin Middlewoods's articles on the front page of a 1992 edition of The Western Front.

- Erin Middlewood featured as the Associated Students president in a 1992 edition of The Western Front.

- Erin Middlewood's article on beauty standards published in a 1992 edition of Klipsun Magazine.

Valerie Bauman (2003)

While earning her journalism degree, Valerie Bauman went to Prague. Lyle Harris, one of Bauman’s favorite professors, encouraged her to go because he taught a travel writing course there.

Bauman spent her last four months of college writing stories for The Prague Post, a weekly newspaper. One of her assignments was to write about libraries, which at first, she thought was just a way to keep an intern busy with a boring story. Through her research, however, she learned about the cultural significance of libraries — Czech people think libraries are “déclassé” and for poor people.

“You own your own books, you collect them, you treasure them, you pass them down through the family from generation to generation,” Bauman said. “[The government] was trying to sexy up libraries and change the way Czech people thought about literature.”

While reporting, she visited libraries with a translator, meeting customers from all generations. She remembers one “adorable” elderly customer who was learning to use the internet for the first time.

“It was a very cool experience that really taught me how to make something out of nothing,” Bauman said. “You get the lamest assignments, but a lot of times, you find your story, you find the character and you turn it into something.”

Bauman graduated in 2003 with a degree in journalism and a concentration in political science. After graduation, she freelanced, which put her in three cities a week. “Just trying to build up clips to get credibility [and] to get a permanent job,” Bauman said. “It was a pretty rough time, I’m not going to lie.”

She was working seven days a week, even freelancing on the weekends as a makeup artist and doing radio news in the early morning. She dreamed of working for the Associated Press, and was applying to a variety of internships to get herself there. She eventually contacted The North Carolina Bureau of the AP, emailing and calling them twice a week for six months.

“I was kind of just relentless,” Bauman said. “I just could tell the [news editor] got a kick out of me.”

She was eventually offered a job.

Through her time as a journalist, she’s seen talented colleagues laid off and newsrooms close. However, she said she also has witnessed an “exciting revolution of new ways to tell stories.” Visual journalism has expanded the industry, through interactive databases, graphics and podcasts.

In 2019, she got the opportunity to work at Bloomberg covering healthcare, which she has a “soft spot” for.

“Everybody dies, and in between, you’re probably going to see a doctor or two,” Bauman said. “I just can’t think of anybody who healthcare doesn’t apply to.”

When the pandemic hit, Bauman was covering healthcare in Washington, D.C. “Mostly pharmaceutical litigation, which sounds boring, but it’s really fascinating,” Bauman said. “It’s everything from drug pricing to the opioid crisis.”

COVID-19 was essentially job security for Bauman, though she wasn’t too excited about pandemic stories because so much of the work was breaking news. She enjoys more in-depth projects, which is why one of her favorites involved creating a database of pharmaceutical company settlements.

Bauman recently transitioned to a new role with Bloomberg as a Senior Investigative Reporter. Though she is used to writing stories daily, she is now tasked with working on long-term projects this year.

“To spend six months to a year working on one project is a privilege that I couldn’t have dreamed of. It’s fantastic,” Bauman said. “I’m really excited to see what I ended up doing with it, but it’s a very different rhythm and I have to be really on task and mindful of how I use my time.”

- Valerie Bauman's article on medical marijuana published in a 2003 edition of The Western Front.

- Valerie Bauman's article on the Everybody's Store published in a 2002 edition of Klipsun Magazine.

Daniel Berman (2012)

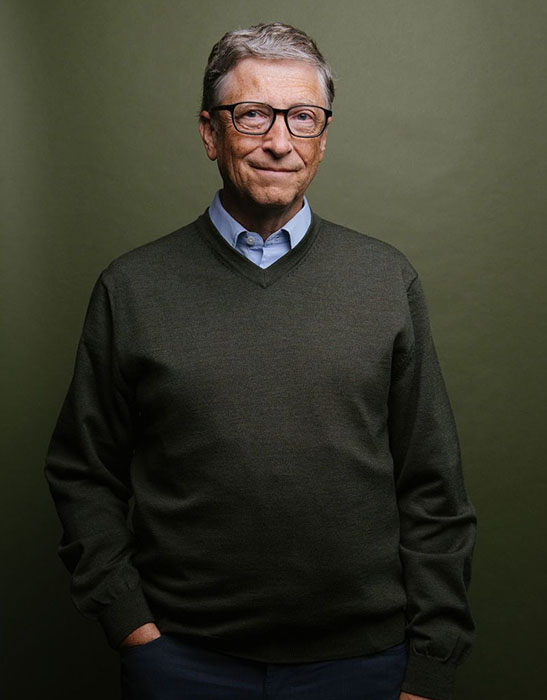

After spending hours planning the photoshoot’s lighting, Daniel Berman arrives with two assistants and sets up. They know they’ll only have four minutes to take pictures, so everything has to be perfect.

Finally, Bill Gates arrives.

Berman walks up to him and reaches for a hand shake. Later, Berman will find out Gates doesn’t like to shake hands. Then, Berman says, “Thank you Bill.” Later, Berman will find out Gates doesn’t like to be called Bill.

However, according to Berman, Gates was “super present” and The Telegraph photos turned out fantastic. In four minutes, Berman captured Gates’ personality perfectly.

“I try and treat everybody with a lot of respect and honesty, and feel out what they need from the photos as well,” Berman said. “A lot of these celebrities have had their picture taken, but they don’t necessarily want their picture taken. It’s all a bit of a dance. So, when I’m on a set and I’m meeting Bill Gates for the first time, I want to just let him know that I’m a human just trying to make a great picture.”

After completing his associates at Shoreline Community College, Berman transferred to WWU with the hopes of being a freelance photographer. He graduated in 2012 under the journalism department’s Visual Journalism track, which he considered the best visual journalism program in the state at the time.

One of the classes he remembers the most is Sheila Webb’s Editing class, J309, which focuses on newspaper and magazine page design. Though Berman’s primary interest was in photography, Webb’s class is where he learned InDesign, which, little did he know, would later help him at his first job.

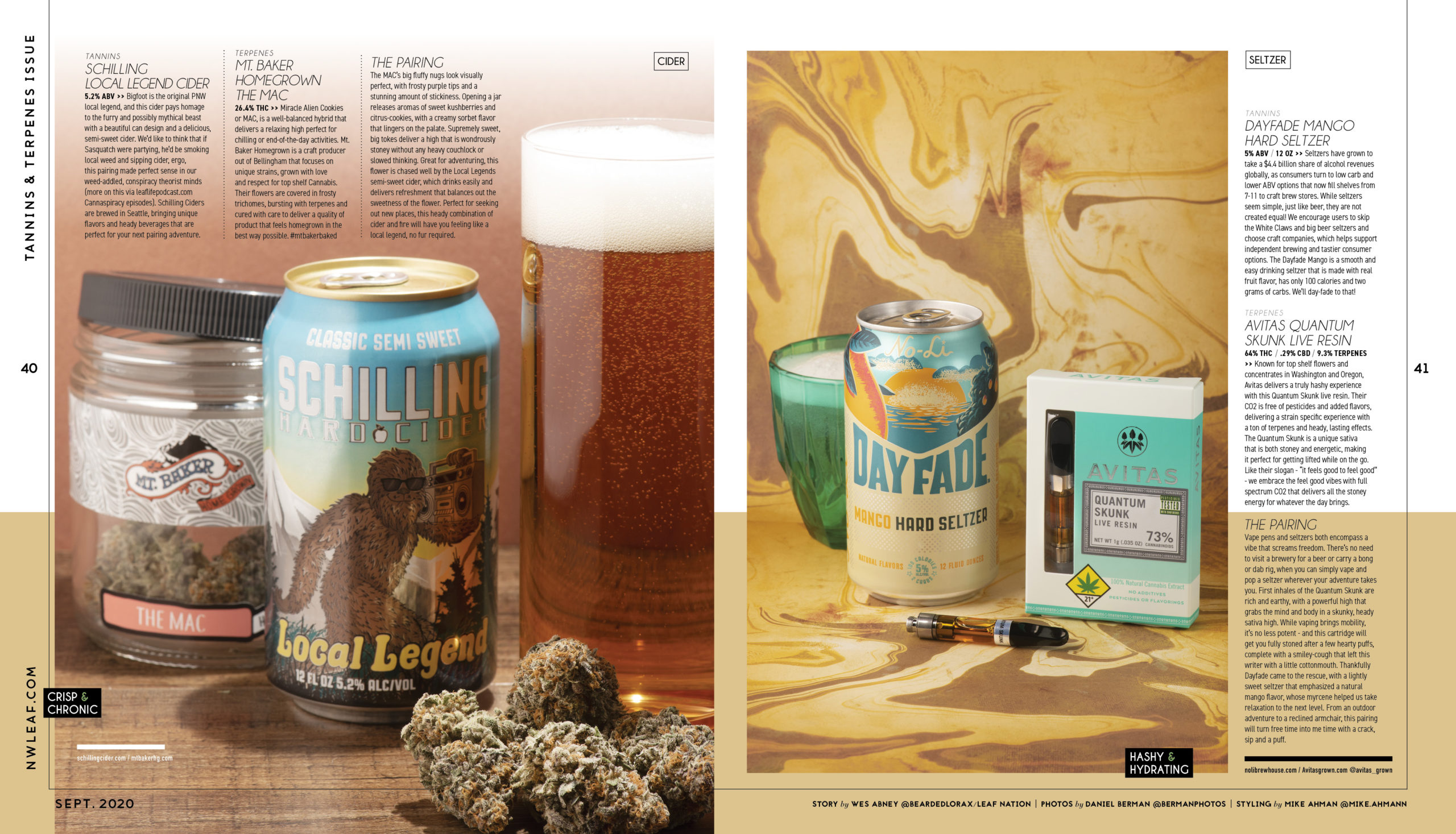

Two years before Berman’s graduation, his friend, Wes Abney, started a Cannabis publication called Northwest Leaf. While taking classes at WWU, Berman traveled to Seattle, Washington on the weekends to work for the magazine. He was applying everything he was learning as a Visual Journalism student to Northwest Leaf. What started as a 16-page newsprint magazine has now grown to six monthly local editions in 14 markets across the country.

Now, as Creative Director, Berman oversees the layout and creation of almost 200 pages of print magazines each month. He assigns photographers, hires illustrators and edits photos in addition to designing pages.

“I’m doing what I love in the field that I always wanted, and the opportunities available to me expanded as a result of just this random class that really kind of changed my life,” Berman said. “If I had not learned page design, I wouldn’t have my role overseeing all these magazines.”

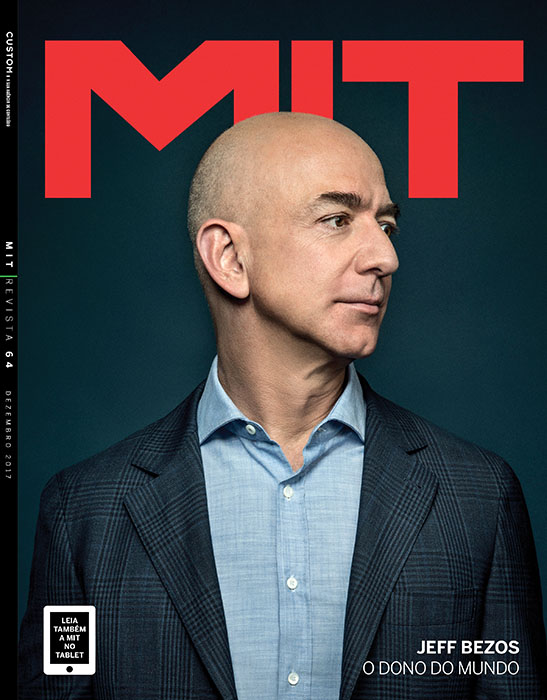

However, Berman is primarily what he always planned to be: a freelance photographer for major companies, newspapers and magazines. In addition to Bill Gates, he’s photographed Jeff Bezos, Steve Ballmer, Snoop Dogg and Tommy Chong.

“I’m always interested in challenging projects, projects that push me and force me to grow,” Berman said. “There’s nothing like getting an email in the morning from a new client you’ve always wanted to work with who found your name from somewhere and thinks you’re right for this project.”

Since COVID-19, Berman’s career has changed and evolved. He is doing more photoshoots where the client isn’t on set and he does remote art direction using Zoom. Though there are limitations to this, it also allows him to photograph people in other areas. In-person sets have smaller crews — everyone wears masks and socially distances. They do as much as they can to create a safe environment for the subject.

To organize the magazine, the staff meets weekly on Zoom. Berman believes they’re working better as a team by taking advantage of new communication tools.

“I was so used to working from home anyway, that not a lot has changed,” Berman said. “So, all these people who had to get used to working from home, welcome to the freelance life.”

(From left to right) Bill Gates, Snoop Dogg, Patti Warashina and Jeff Bezos. // Photos by Daniel Berman